janethesturgeon

,

delano and morrison, vertigo and detective comics

discussing the ghost of politics in superhero comics

While Morrison’s Action Comics, and even their Batman, are representative of less deconstructive works in Morrison’s career, their earlier work in Doom Patrol or The Invisibles falls much more in line with the critical bent of Delano’s Hellblazer. DC comics have always been concerned with weaving tapestries of contemporary myth from its inception with Superman and Batman, to Kirby’s Fourth World saga of Darkseid and Highfather. DC’s mythos, for it is a mythos, has remained in many ways unchanged from the early twentieth century to the contemporary period as can be seen in Ram V’s New Gods and Detective Comics runs.

In opposition to the greater DC imprint, the Vertigo Brits were doing the dirty work of the contemporary folktale and fairy story. What are Invisibles and Hellblazer if not paranormal magazines akin to UFO Magazine or 3rd Stone which. Hellblazer and Invisibles make less claim to journalism, but the work on their pages holds a tone of unveiling mysteries which one is more likely to find in the pages of the Journal of Parapsychology than in Superman. Herein lies much of the contrast between the British postpunk movement of the late twentieth century and very American arena rock of the same period. The latter markets a legend, and idealized form in the face of which we might feel a sublime smallness. In the pages of Superman we will always be the small, nameless child rescued from an out of control car, in much the same way that under the lights of a Bon Jovi concert, one might feel the safety of being one of the millions saved, awe-struck in the face of gods. In the former, in the grungy club, lost in the trance of an industrial beat, we are made small but also made a part of the thing itself. This is the key allure of The Invisibles, for instance, that we might recognize our smallness in the vast whole, but that we might cry out nonetheless, and that the vast whole might have no choice but to hear, and to cry back.

towards a postpunk superheroics pt. 5

In my last post I stated that it was Hellblazer’s essential ‘Britishness’ that really distinguishes it from the classic American superhero comics and not a difference of structure or character. I want to discuss this in a little more detail, and lay a groundwork analysis of the Americanized superhero in order to better get at what makes Constantine distinct from, say, the Flash.

Superheroes originate, and remain, a deeply American form. That is not to say that non-Americans cannot or have not written excellent superhero stories. If that were the case, there would be nothing to write about in this blog. The fundamental Americanness of superheroes lies in several factors. For one, they originated in large part as US war propaganda and a means to sell war bonds effectively during WWII. They were unabashedly pro-involvement, and anti-Nazi, and they remain for the most part deeply invested in a belief in violence, war, and the ultimate power of the law to determine justice. This fealty has waxed and waned over the years and across characters, but one need look only at any handful of superhero comics to see that the police are part and parcel to most.

American superheroes also exist in a kind of atemporal a(dys)topia in which contemporary politics is rarely allowed to invade the realities of the universe. Exceptions include explicit references to Hitler and World War Two in early Marvel comics, as well as more recently 9/11, which was given a famous special one-shot issue. These examples are excellent indicators of how the American superhero comic has evolved over time.

Joe Shuster, Jerry Siegel, and Jack Kirby, all men hailed as titans of American comics, given the kind of canonical status in the form that Dickens has over the novel, or Christ over Christianity, were all Jewish artists and writers creating overtly political work. Comics at the time existed as a solely pulp medium. They were not, as they are today, multi-billion dollar industries which produce intellectual property for even larger dynasties like Disney, Warner Brothers, and Sony. The political leanings of these creators were unabashed and uniterested in censorship. These creators were not anesthetized to the market forces of sales, which were boosted by Captain America or Superman punching Hitler, but they were also driven by real political conviction.

Take, now, the J. Michael Straczynski’s Amazing Spider-Man #36, in which, brought together by the tragedy of 9/11 heroes and supervillains, along with NYPD officers, and firefighters all attempt to help however they can in the aftermath of the destruction of the twin towers. Unlike the kind of straightforward explicit political stance of Kirby’s early work, Straczynski’s issue is obsessed with American victimhood. The 9/11 attack exists as an all-unifying force across the Marvel universe. In one panel, villains stand together in the wreckage, united with the heroes in the face of atrocity. Among them stands the Kingpin, a psychopathic serial killer, Doctor Doom, an authoritarian dictator from another continent, and Magneto, a genocidal villain who has done just as bad and worse. Morality and narrative are put on hold for what is an incredibly jarring intrusion of a real world event into an otherwise contained storyline. The absurdity of the superhero industry is put on full display by the issue, as they’ve abandoned any kind of narrative loyalty for the 9/11 issue.

What’s more, the comic is embarrassingly politically lukewarm. It makes weak assertions that 9/11 wasn’t the fault of gay people or feminists in the US, and neither is it the fault of ALL muslims, just a lot of them. What’s most notable and disappointing is that Marvel has simply given up on attempting to address actual politics through narrative and fiction, and instead made the surreal choice to make a “Spider-Man 9/11.” This ideological lack of commitment iis a hallmark of the modern and contemporary superhero story, and was such a dominant force in American comics from the 1990’s onward that nearly all American attempts to create new superhero comics, from the likes of the Image founders for instance, was never able to escape the apolitical swamp.

It took Karen Berger, someone entirely disinterested in superheroes and American cartoonists to open the door to our postpunk superheroics.

janethesturgeon, November 16, 2025

on jamie delano’s john constantine: hellblazer

towards a postpunk superheroics pt. 4

It's getting faster, moving faster now

It's getting out of hand

On the tenth floor, down the back stairs

It's a no man's land

Lights are flashing, cars are crashing

Getting frequent now

I've got the spirit, lose the feeling

Let it out somehow

-Joy Division, “Disorder” Unknown Pleasures, 1979

Works like Morrison’s Action Comics run are good primers for the endpoint of the British invasion’s postpunk works, as they represent the final work of significance, as of yet, that Morrison has put out, with their more seminal comics like The Invisibles, Doom Patrol, Batman, and New X-Men being works that require a much larger scope of study. Action Comics is far and away one of the simplest works from this era of writers and cartoonists, but also represents a distillation of many of the technical, formal, and narrative concerns that they and their contemporaries approached in greater detail in their earlier work which I will begin to discuss here.

Jamie Delano’s run on Hellblazer stands as one of the greatest achievement’s of DC’s Vertigo imprint, the imprint which would house many of the foundational voices of the era including Morrison and Alan Moore. Much like Moore’s Swamp Thing, or Morrison’s Doom Patrol, Delano’s run is often hailed as the greatest era for the Hellblazer comics. Delano’s partnership with artist Sean Phillips makes for some of the most fascinating postpunk superheroic comics of the era.

Hellblazer slots into the moniker of postpunk superheroics more easily than something like Swamp Thing or All-Star Superman in large part due to its undeniable Britishness; the series centers a British man(John Constantine) who uses largely British pagan magics in a Thatcherite Britain in which the old powers of the natural world are being superceded, corrupted, and killed by the ravages of authoritarian capitalism. Hellblazer voices and dialogues with many of the same concerns of the literal postpunk musical movement, which spawned from the brutal conditions of being working class British under Margaret Thatcher, the Troubles, rising xenophobia, homophobia, and a general decline of the perceived greatness of the empire. Delano’s run on Hellblazer along with Garth Ennis’s, on which I shall write later is the center of this milieu, conjuring monsters both human and magical, reflective and representative, of Thatcherite Britain and its hellish offspring.

John Constantine, the eponymous protagonist of the Hellblazer series, is a chainsmoking, traumatized, and cynical magician who wanders Britain in a trenchcoat helping people when he can, and getting swept up in the tides of battle between good and evil. The character was originally created by Alan Moore as a supporting character for Swamp Thing, but it was Delano who really made the character into who he is writing the first forty issues of the series under the editorial direction of Karen Berger. Both Berger and Delano have spoken passionately about Hellblazer as being fundamentally distinct from the superhero genre, but I would challenge that assertion for a number of reasons. For one, it reeks of a superiority complex regarding superheroes which irks me. The second, more tangible reason, is that Hellblazer is structurally and formally not so distinct from superhero stories, and their older genre counterparts from traveling knight romance stories to Wuxia tales and pulp westerns. Constantine is a superpowered vigilante who travels around helping those in need. The adversaries he faces are often, but far from always, distinct from those that Batman or Superman face on any given day, given that they’re often demons, psychopaths, or extradimensional monsters.

What differentiates Hellblazer from Spider-Man is the postpunk essence of Delano’s work; a kind of fundamental lack of trust in the permanence of good, evil, power, love, life, and even place. There’s a letting go of the ties that bind in Hellblazer reminiscent of a Joy Division song, or dancing in a dark sweaty club to a Cure ballad. Whereas Morrison rejects the laws of form and reality and Action Comics with the kind of clean-cut tenacity of someone who is a comics believer, Delano rejects it with the kind of scrawny dirty tenacity of a punk thrashing in a mosh pit.

janethesturgeon, November 14, 2025

grant morrison’s action comics

towards a postpunk superheroics pt. 3

As I’ve discussed below, sincerity, rather than cynicism, is the driving force of much of Morrison’s superhero work, which sets him apart from his most notable counterpart Alan Moore. I argue that the sincerity which drives the superhero genre, especially in DC comics, is what has set them apart from wider academic and generic discussion of them as a member of the science fiction family. Instead, superhero comics, while generally shunned critically, are also not allowed entry into science fiction, being classified as their own genre. While understandable, I think a study of Morrison’s work through the lens of high concept sincere science fiction, akin to the sincerity more commonly found in early fantasy(Tolkien, Leguin’s Earthsea) and early pulp science fiction, is valuable in understanding Morrison’s treatment of Superman specifically in Action Comics.

The climax of Morrison’s Action Comics run is a battle between Superman and the five-dimensional villain Vyndktvx. During this climax we learn that the many foes Superman has faced in the issues leading up to this have all been orchestrated as grand magic tricks by a fifth dimensional court jester Mxyzptlk. Superman himself, Morrison reveals, is Mxyzptlk's favorite trick, because superman always manages to foil the evil plots of Vyndktvx, Mxylpltk’s jealous rival.

What’s notable about this reveal is that Superman’s story is not lessened in importance or grandeur for being simply a court jester’s favorite trick. Rather, it’s Superman’s incredible ability to overcome even the insurmountable power of such a being that asserts his narrative grandeur. The fifth dimensional imps in Morrison’s story act as fantastical stand-ins not for us as the readers but for Morrison themself, as the creator of a story greater than themself. We know that Superman is not real, as does Morrison. He is ink on paper, and yet he is not reduced. Rather, he is uplifted. Morrison’s Action Comics acknowledge this two-dimensionality, this fiction as a way of underscoring just how powerful Superman is beyond the page, his strength reaching beyond the two-dimensional plane of the comics page, and into the three-dimensional one of our own lives.

The permeability of Morrison’s boundary between second and third dimension, comic and reader, superhero and human, reflect Morrison’s optimistic understanding of the superhero genre not as a naive form in need of deconstruction bordering on demolition, but rather as literally the ultimate destination of humanity itself.

janethesturgeon, July 22, 2025

grant morrison’s action comics

towards a postpunk superheroics pt. 2

Understanding this melding of postmodern, irreverent deconstruction of the Superman story, and Morrison’s own reverent reconstructive preservation of the Superman story. In my last post I briefly mentioned Morrison’s view of superheroes as, very literally, the modern gods of humanity as a whole. For him, the ultimate members of this pantheon, those who most closely correspond to say, the greatest gods of Mount Olympus, are the Justice League of America(JLA). I’ll talk about Morison’s run on JLA later in this series, but in order to discuss Morrison’s JLA it’s important to look at his depictions of the team’s central figure: Superman.

Morrison’s run on the New 52’s Action Comics is notable because it sees the writer being given free reign to build Superman’s origin from the ground up in a new continuity for DC Comics. Rather than rewrite a hero’s origin story to make the character more culturally relevant, make a social critique, or critique the genre itself as writers have done in cases such as Marvel’s Ultimate universe, DC’s Absolute Universe, or, arguably Watchmen itself, Morrison steadfastly insists on the sanctity of Superman’s original character.

This alone, however, isn’t particularly of note. Mark Waid’s run on Flash, for example, shares a similar flavor of fundamentalist respect for its titular character. What I find so fascinating about Morrison’s particular brand of dedication to Superman’s building blocks is that the very climax of Morrison’s run on Action Comics is so deeply concerned with the metaphysics of the comics medium. I find it somewhat daunting to engage with Morrison’s understanding of the comics medium in large part because they see comics as being an accurate representation of the substance of time itself. Morrison isn’t the only cartoonist or comics scholar to note that comics is one of the best, if not the only, narrative medium that challenges, on a fundamental level, linear time. Several notable members of the British invasion, in fact, made work very concerned with this very concept, although none as obsessively as Morrison.

Morrison argues that we should understand comics as a two-dimensional representation of the flow of time itself. He understands the continuity of the comics page to be the most accurate depiction of time that three-dimensional beings(humans) can create without actually being able to see time(the so-called 4th dimension), as a 5th dimensional being could. In the climax of Action Comics, Morrison makes their imagined fifth-dimensional beings characters in the two dimensional pages of the comic. These godly beings who can not just reach into and manipulate the second dimension as we can, but the third and fourth with ease are the facilitators of Superman’s confrontations with his many metatextual(multiversal) selves. It’s this canonical confrontation, which treats Superman not as a thing to be manipulated by Morrison, but instead honors unimpeachable sanctity of his character, and the reality of his power.

janethesturgeon, July 20, 2025

***

grant morrison’s action comics

towards a postpunk superheroics pt. 1

Action Comics is a pair of words as important to modern American culture as We the People. It’s almost impossible to fully understand the cultural significance that the American superhero genre has had on the American psyche over the last eighty or so years. The evolution of superheroes which were spawned in the early twentieth is a subject which Morrison is deeply concerned with.

In Action Comics, Morrison creates a postmodern deconstruction of Superman, engaging in a metatextual dialogue with the several historical stages of the Man of Steel. At the same time, however, Morrison has a literal reverence for the heroes he is tasked with writing. More on this in a later post but to Morrison, superheroes are on a very real level, the pantheon of humanity. A kind of deific future towards which humanity moves.

This meta-portrait plays out across multiversal versions of Superman, rather than the central ‘real world’ Clark Kent with whom we spend most of our time. The central Clark represents the character of the original Action Comics, or at least, how Morrison sees him. Superman in this iteration is a labor hero.

This Clark wears double-kneed work pants and a t-shirt. Despite his alien biology he is in a much deeper emotional and psychological sense, human. It’s in this humanity that Morrison’s reverence for his characters is most readily apparent. His dehumanization by the billionaire Lex Luthor is thus an allegory for the dehumanization of working class people who, in this idealized deified version of humanity, is able to break free of Luthor and the military’s chains and choke out some billionaire throat.

Action Comics #4, Grant Morrison & Rags Morales, DC Comics

Morrison, as I’ll continue to write about, exists as a transitional member between the postmodern and metamodern eras of the superhero canon. As a pivotal member of the British Invasion of the eighties who continued to write massively popular superhero comics well into the 2010s, he stands in contrast to writers like Allen Moore, arguably the most important member of the British Invasion and certainly the most famous, who sought to deconstruct and critically(cynically?) reframe the genre as a whole.

janethesturgeon, Jul 16, 2025

***

eddy atoms pinky & pepper forever

I’m a sucker for any art that makes me aware of it as something that was made. I love Brecht, whose theater is all about making you aware that you’re watching a play, or Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee, which is admirably dedicated to stopping you from losing yourself in its language. Eddy Atom’s newest book, Pinky & Pepper Forever(Silver Sprocket 2025) is such a comic. The story is about Pinky and Pepper, a lesbian couple of anthropomorphic dog girl art students who end up dead in hell, training to be grim reapers.

The art is hyper-stylized and incredibly campy, drawn with various media including several kinds of paint, scratchy colored pencil, digital art, and even a sculpture. In a book populated by less frenetic characters, driven by a more subdued plot, this kind of change would be jarring, but in Pinky & Pepper Forever, the style is illustrative of the wild subjectivities of suicidal, BDSM-obsessed puppy-girl lesbians.

Like many stories about artists, Pinky & Pepper Forever has a meta narrative woven throughout the book. The intense, psychedelic colored pencils of Atoms’s world don’t just reflect the fun colorful mania of his two protagonists, but also the ways which artists hyper editorialize their own lives, turning them into Narratives, rather than face the intrinsic unpredictability of lived reality. Such editorialization takes on a more sinister note when paired with the obsessive toxicity of Pinky and Pepper’s relationship as the story develops(Pinky ends up committing suicide to spite Pepper, whom Pinky believes doesn’t appreciate her art, turning her body into an art piece).

Their relationship is a combination of melodrama and kitsch, emotionally intense enough to end in suicide, fraught with all the very real complexities of a queer relationship, and yet also about as mature as two children fighting over a toy truck on the playground. It’s this interplay from which much of the campiness of Pinky & Pepper stems, fueled by Atoms’s beautiful, affected art style. As a kitsch art object, Pinky & Pepper Forever is a wild success.

Unfortunately, the narrative complexity of Atoms’s work gets lost in this sea of camp. The themes of victimhood, self-worth, art, and suicide, all within a queer relationship don’t get the room they should to breathe, ending abruptly in a rather forced “happy” ending. Our introduction to Pinky and Pepper’s relationship is so fast that we don’t get a chance to understand their status quo before they fall apart. This problem persists throughout the story, with each story beat feeling over before it’s begun. The pace adds to the whirlwind, manic feeling of the two’s relationship, but reading a book centering queer relationships and suicide without being allowed an emotional attachment to the characters and their struggles is frustrating.

janethesturgeon july 5, 2025

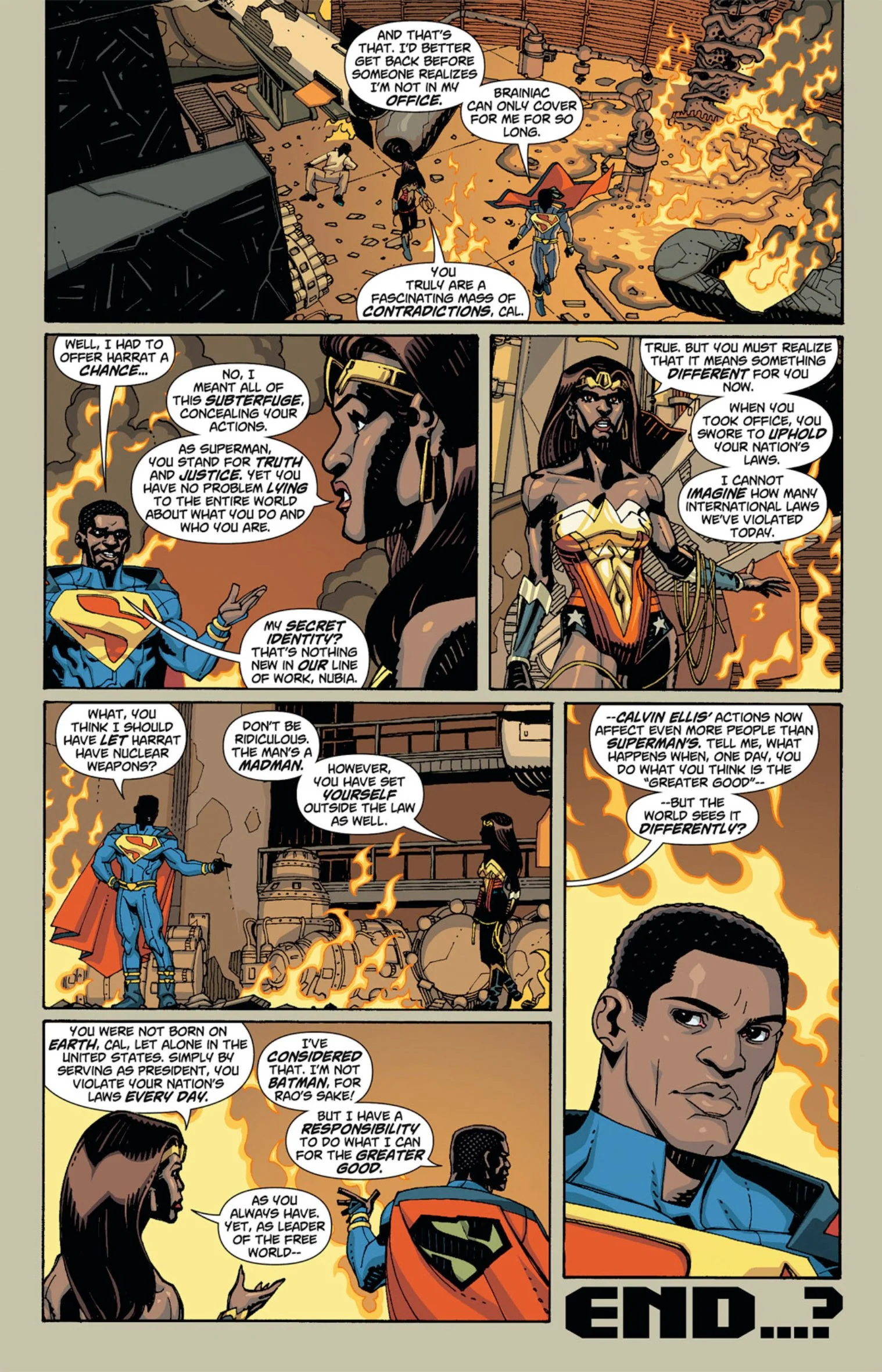

This nonlinearity can be illustrated by looking at this page from New 52 Action Comics #9

The “first” panel is generally understood to be the panel at the top of the page. From there we move left to right, top to bottom.

But should you ask Calvin Ellis Superman in any given panel, there is no first, second, or last panel, as every moment is the present.

Furthermore, one can’t help but see the entire page in an instant, understanding the the scene as an entire single moment, rather than a linear timeline.

Further time bending can be done, but the basics have just been covered.

You can’t do this with film or prose, both of which rely on a linear reading/viewing process.